The corporation tax increases to 25% from April 1st, 2023, for any business that earns more than £250,000 in profits within a tax year. However, the rate will remain at 19% for profits below £50,000. Any profit amount between £50k-£250k will be taxed at 25% with a relief applied to reduce the amount paid. According to the Government, the UK’s corporation tax system will remain the most Generous in the G7.

However, this change is one of the biggest made to profit tax in decades and will make the UK slightly less competitive in the eyes of foreign investors. The incoming changes is also no longer a “one size fits all” approach and will add an additional layer of bureaucracy and complexity to the process of paying tax, likely impacting smaller business more in terms of cost. Some might even remember that the use of upper and lower limits to classify corporation tax is something that’s not been seen since pre-2014.

However, the limits are variable depending on different scenario’s, such as accounting periods being less than 12 months or if a company has one or more “associates”. The impact of associations could be beneficial or more burdensome depending on the business’s situation

What is an ‘associate’ company?

A company can be associated with another company if at any time within the preceding 12 months one company has control of the other or if both are under the control of the same company or person(s).

The key criteria here on whether a business will be classified as associated is the definition of control. In other words, if one company or person exercises, can exercise or is entitled to acquire or direct control over another company then that company would be seen as associated. This includes having access to share capital, voting power, rights over the company’s income etc.

Such relationships are common in business with shareholder ownership structures. For example, private investors who directly own shares of multiple companies or Private Equity firms that own a portfolio of businesses of which the firm can exercise operational control over each of them. Generally, this would require a 51%+ equity ownership of each associated business, but the definition used here is slightly wider if individuals or businesses are able to exercise control even without majority ownership.

There is a concern that the usage of associations in company ownership to dictate tax treatment may have a negative impact on businesses and the tax they pay for being associated with other companies. For instance, the upper and lower limits for corporation tax (£250k and £50k) are proportionally reduced based on the number of associated companies a business, or person, has. If your business is associated with 1 other company, than the upper and lower limits for corporation tax are reduced to £125,000 and £25,000 respectively for each business. Similarly, if your business is associated with 4 other companies, than the upper and lower limits will fall to £50,000 and £10,000 respectively. This methodology splits the available benefit, or tax allowance, that is typically available to one firm between multiple associated companies.

The impact of this is it reduces the level at which the 25% tax rate on profits is guaranteed to kick in without access to any marginal relief and reduces the profit allowance at which corporation tax remains at 19%. This raises concerns for businesses, specifically growing SMEs who are likely to be involved in associated connections. In certain cases, this can result in the total amount of tax that is payable in one 12-month period being higher, than would be the case if only one company was being taxed on its profits.

An example

Two manufacturing SMEs, company A and B are associated companies. Since company A is associated with company B, the upper limit at which the 25% tax rate begins (without marginal relief) decreases from £250,000 to £125,000. In this scenario both companies are assumed to make the exact same profit, there the total augmented profits are at £150,000 (£75,000 each). For the purposes of these examples the impact of dividends is not included and will not consider the impact of more than 1 association. However, for 2 or more associations the examples below will apply similarly.

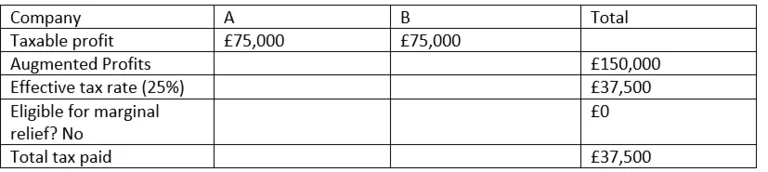

The below table highlights a basic example of two associated companies paying corporation tax on their profits (assuming the tax year starting 1st April 2023 to 31st March 2024).

Table 1

Under this scenario the total tax paid would be £37,500. However, if company A and B were not associated, and operating as separate entities where neither party or a 3rd individual had “control” of these companies then they would be taxed separately with the original thresholds (between £250,000 and £50,000) applied. That scenario is illustrated below in Table 2 for company A.

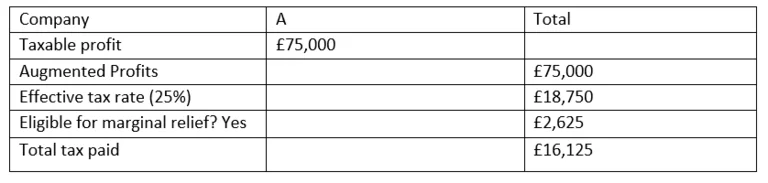

Table 2

In that situation (Table 2) where both companies are ‘un-associated’, company A would have a tax liability of £18,750 (and be eligible for £2,625 marginal relief) resulting in an effective tax rate of 21.5%. The same would be true for company B, together the total tax paid by both these companies would be £32,250 (£5,250 less than in the situation where these businesses are associated).

In conclusion, both company A and B could be better off being separate un-associated entities for the purposes of corporation tax.

Does the ‘associated’ company rule also impact large businesses?

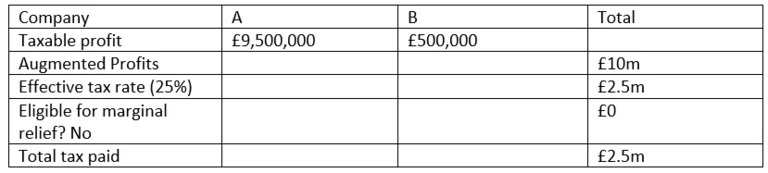

Let’s say there are two new companies, still A and B, but these are larger manufactures making much greater profits (Table 3).

Table 3

Now, if these larger businesses were not treated as “associated” and taxed individually then company A would pay £2,375,000 in tax, whilst B would pay £125,000 in tax (totalling £2.5m) suggesting the associate rule between two or more large businesses may not have a negative impact on tax liability. The same is going to be true for two associated micro businesses that are taxed at the lower 19% rate that make profits below the lower threshold (£25,000 in this case). The scenario above identifies an association between only 2 firms, for example, Large + Large or Micro + Micro. Of course, the difference between large, small, or micro businesses is mostly irrelevant for these cases as even a large business can make small profits. However, these scenarios hold the view that it is smaller companies that are more likely to make smaller profits, but this may not be necessarily the case every year.

The indirect cost of association

The consequences of this incoming rule change could have detrimental impacts on the flow of investment towards growing SMEs as potential investors, whether they are a company or individual, may see less benefit in taking majority ownership of these companies if it could lead to higher tax liabilities. By introducing upper and lower bounds combined with the associated company rule, Government has effectively created a middle population that is worse off in certain cases.From this perspective, whilst the move is likely designed to prevent malpractice and tax avoidance it will lead to some businesses being caught in the middle, even if they themselves do not have any intentions to avoid paying taxes and subsequently end up paying more if they are associated. It is possible that the complexity of this rule would motivate investors to target investment opportunities for more meaningful reasons, rather than for purely tax benefits which may result in some long-term benefits.

What should the Government consider next?

Considering the implications of these changes, Government could include a type of enhanced relief to boost the marginal relief which would ensure that associated businesses within the thresholds do not at least pay more than they would if they were un-associated, whilst still preventing the system from being abused by those that intend to reduce their tax liability.Disclaimer: This article only seeks to inform and does not constitute as tax advice for readers. It is advised you speak to a professional tax advisor for solutions specific to your business.